Restoring Hope Amid Ecological Collapse

From collecting native seeds to retiring groundwater used for farming, the Walker Basin Conservancy is pulling out all the tools in the toolbox to restore Walker Lake and its fishery.

With an annual average precipitation of just 10.3 inches, Nevada is the driest state in the nation. That makes it challenging for water managers to monitor, restore and protect the state’s waterways for agricultural and industrial use, while still maintaining enough for recreation and ecological protection.

Take central Nevada, for example. Over the last century, the Walker River Basin has gone from a healthy ecosystem that supported many agricultural and economic activities to total ecological collapse.

“To put it real succinctly, upstream diversion has lowered the flows of the river entering Walker Lake, and as the flows have gone down, the lake level has subsided. The water evaporates out of the lake, but the salt does not evaporate out of the lake, and because of that, the salinity has increased over time,” said Peter Stanton, CEO of the Walker Basin Conservancy, a nonprofit organization working to repair and restore the area.

While it sounds dire, Walker Lake is recovering, thanks in large part to the work of Stanton and his team.

“We’re working on a very ambitious project to increase the flows of the river and restore Walker Lake,” Stanton said. “Walker Lake itself is a real gem for the region and near and dear to the heart of a lot of Nevadans and a lot of residents for a long time.”

Stanton said since the beginning of 2023, the lake has risen by 16.5 feet, and as it stands now, 57.5% of the water needed to restore Walker Lake has been acquired.

Sierra Nevada Ally Executive Editor Noah Glick recently caught up with Stanton to learn more about what the organization is doing and how they’ve been able to turn collapse into hope when it comes to Walker Lake.

Sierra Nevada Ally: What is the Walker [Basin] Conservancy? What do you guys do, and what specifically is your role?

Stanton: The Walker Basin Conservancy is an independent Nevada nonprofit organization that works to increase the flows of the Walker River in order to restore a fishery at Walker Lake. My position is Chief Executive Officer with the conservancy, so I do a little bit of everything.

Most of our work is in what we call environmental water transactions, and that’s really taking former irrigation water rights and converting them to protected environmental flows of the Walker River. In addition to that water work, we do a lot of on-the-ground ecological restoration as well, so a lot of reestablishing habitat on former alfalfa fields, quite a bit of public lands work throughout the Walker River Basin, habitat improvement projects, quite a bit of rare species monitoring, that kind of work as well. And then we also own and operate a ranch and now a native seed farm in Smith, Nev.

We have about 30 employees currently, plus an AmeriCorps program. It’s a big effort. We’ve been doing this kind of work for about 10 years. All together with our predecessors, the work in the Walker Basin restoration program has been going on for about 15 years now.

For those who maybe aren’t super familiar with Walker Lake, can you just tell us a little bit about the lake? Where does it fit into the overall water picture and what watershed is it a part of?

We’re talking about the Walker River watershed, which spans California, eastern California and western Nevada. We’re basically starting at the eastern border of Yosemite, at the Sierra Crest. The east and west parts of the Walker River wind through a total of four agricultural valleys – two in California, two in Nevada – and then on through the Walker River Reservation in Nevada and on to Walker Lake.

Walker Lake, as late as the 1980s, supported about 50% of the Mineral County economy. There were fishing derbies, there was an annual loon festival, there were charter flights from Southern California up to Walker Lake to fish for Lahontan cutthroat trout. Fishermen in the area call them LCT or cuddies, it’s a huge part of the heritage of Northern Nevada, a huge part of the fishery of northern Nevada. And it’s also had a lot of cultural importance for our region as well.

The Walker River Paiute Tribe has lived on the north shore of Walker Lake seasonally for thousands of years, and there are human artifacts surrounding Walker Lake dating back approximately 7,000 years. In their native language, the Walker River Paiute tribe referred to themselves as a Cui-ui, or trout eaters, and the Walker Lake as Agai Pah, or trout water. So really, going back thousands of years speaks to the importance of a trout fishery at Walker Lake and throughout the Walker River system to this region.

Beginning with European arrival, starting in the 1860s and Mason Valley, we start seeing upstream diversions of the Walker River for irrigation purposes. Shortly thereafter, people started noticing the effects on Walker Lake. The earliest account that I’ve seen of the impacts of the upstream irrigation on Walker Lake date to a USGS report in 1885. So, we’ve known for a while that upstream agriculture is not compatible with a healthy ecosystem in the region.

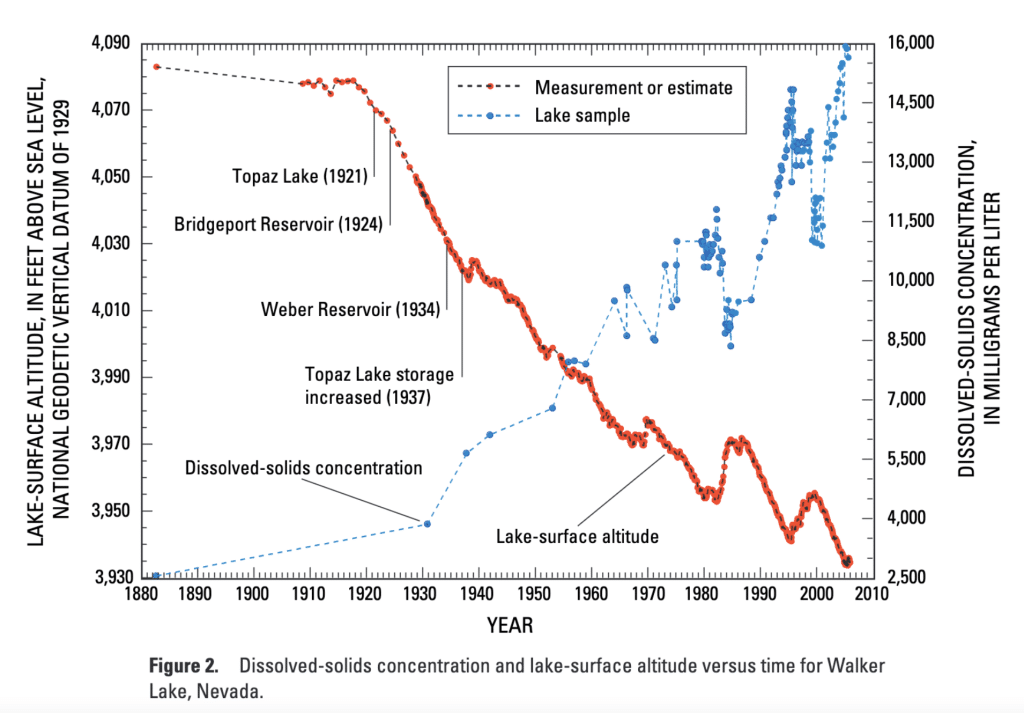

Editor’s Note: A 2007 report from the U.S. Geological Survey showed that, “Since 1882 diversions have reduced flow into Walker Lake which contributed to a decline in lake-surface altitude of about 150 ft and an increase in dissolved solids from 2,500 to 16,000 mg/L since 1882.”

Stanton: As the flows have gone down, the lake level has subsided. The water evaporates out of the lake, but the salt does not evaporate out of the lake. And because of that, the salinity has increased over time. The last Lahontan cutthroat trout that we know of was caught in Walker Lake in 2009 and there is currently no fish life of any kind in Walker Lake.

We say that the lake and the lower river system are in a state of complete ecological collapse. With the disappearance of fish life, we see a significant, huge, I mean, orders of magnitude decline in bird life and migratory bird stopovers on Walker Lake. There hasn’t been a loon festival since the late 2000s in Hawthorne.

So, what’s the status of the fishery right now? How close are we to getting the lake back to achieving a sustainable fishery?

As I mentioned, the last trout was caught about 15 years ago. We’ve seen sustained declines in Walker Lake throughout the 2010s. We’ve had some wet years and last year, 2023 was truly, in many ways, a miraculous year, right? We saw record discharge of the Walker River, and the Walker Lake came up to date from the beginning of 2023 to today, it’s up about 16 and a half feet. That’s due to a record year last year and an above average year this year, along with some of the environmental water transactions that the Conservancy has facilitated or done directly.

We still have a ways to go. Our goal is about where the lake was in the year 2000, that would give us a salinity that would allow us to sustain a Lahontan cutthroat trout population in Walker Lake. To do that, the lake’s got to come up another 23 feet. So, we’ve definitely got our work cut out for us. We keep praying for rain and praying for snow in the region. Mother Nature can definitely help out here. But we’ve really been pleased over the last year, especially to see the momentum building among farmers and ranchers participating in increasing the flows of the Walker River as well.

I’m really interested in learning more about the transactions and some of the water rights. There was a recent transaction that you guys were part of to protect more than four cubic feet of water per second. So how did that come about? What does that mean?

Yeah, we were very excited to announce a new transaction that will protect four cubic feet per second of water rights, instream, for environmental benefit. In general, we work with farmers and ranchers on environmental water transactions in many different ways. To date, we’ve worked with 156 farmers and ranchers mainly on leases. So those are year-long leases in which we lease water from Bridgeport or Topaz Reservoirs, and instead of using them for irrigation, [we] send that water through the Walker River system and on to Walker Lake.

In addition to those temporary leases, we have done 24 permanent water rights transactions, and that’s taken many different shapes, from transactions in which we’ve purchased water rights and converted them to instream flows, to transactions where we’ve purchased water and land, and water and somebody else has purchased the land and kept it in production, or water and land and we’ve created a state park on the land. All together, we have purchased on an annual basis, about 28,000 acre feet per year of water. A typical residential lot in suburban Reno is maybe 1/3 of an acre, something like that. So that’s enough water to cover about three residential lots in about five miles of water. It’s a very large volume of water, and one of the most ambitious projects in North America to increase stream flows.

We’re working on getting all of that protected instream as environmental stream flows. And that’s about 57.5% of the water that we need long term. So, we still have our work cut out for us, more water to acquire, more water to protect instream. But this year, in the last 12 months, we’ve announced two sizable transactions, and it’s a clear indicator that people are still interested in participating in this program, and that there’s still opportunity to do this kind of work to increase the flows for future generations.

I want to ask about what those conversations are like with a landowner, a rancher, a farmer. What’s the sales pitch? You go to a farmer and say, ‘Hey, I know things are dry. Groundwater levels are not where they could be. How about instead of using all of this water for irrigation for your farmland, how about you give some to the Walker River system?’ What’s that like working with farmers and ranchers?

It’s so individual. It really is more about building relationships and understanding individual farmers’ and families’ needs and their intentions, and finding creative ways to meet those needs, right? Throughout the system, I think over the last 15 years, we’ve done a decent job of getting folks on the same page that long term water supply in this region is a threat to all of us. And I see Walker Lake as a barometer of the resilience of this region. We’ve either got a lake that is going up and it’s a sign of health and sufficient water supply for our region, or we’ve got a river that’s going dry, and frankly, if it’s getting drier, it’s going drier closer and closer to our agricultural valleys, right? Overall, I really see the program as a sign of resilience for the region.

It’s important to note all of the transactions that we do, we do at fair market value. That’s a real big stipulation of how we work and how an effective water market works. The things that bring people to the table are the things that drive general changes in real estate and general changes in business, and that’s generational change, changing economies and changing environments. So, I’ll start with treating these as exclusively business transactions.

Most of the acreage from which we’ve acquired water rights has been hay, they’ve been hay fields. Inputs are up, hay is down, and water years are more and more variable every year. What determines the long-term viability of that kind of farming operation? It’s not just a linear function of, ‘Oh, we got this much water this year, so we grew this much hay, right?’ It’s how many years over a given period are we below a viable threshold for water supply. And in a system like the Walker that’s highly variable, highly dependent upon Sierra Nevada snowpack, it’s challenging. I think we can quibble about climate change in farming and ranching communities, but I don’t know a single farmer or rancher who hasn’t told me that the wet years are wetter and the dry years are drier, and that those extremes are happening more often. And as we see that, we start to see implications on the long-term viability of small, independent hay ranches. I really think it’s exaggerated in an area where natural water flows play such an outsized role in the viability of a given business operation.

I want to ask about the native seed program. What is that about and what are you all working toward?

There’s really two big components to what we’re doing in the native seed space. First and foremost, I mentioned we do a lot of on the ground restoration work, and one of the things that was immediately apparent when we set out trying to reestablish meaningful habitat on roughly 5,000 acres of former alfalfa fields, is that there’s not sufficient native plant material to do that. So, we started a native plant nursery and wild collecting seed, in partnership with the BLM (Bureau of Land Management), to be able to provide that plant material ourselves. [We] have seen just a huge increase in overall efficacy with plant material where we know where it’s sourced, it’s sourced from appropriate places and plants that are adapted to the Walker [Basin]. We some regions get five inches of precipitation a year, super arid, very hot conditions beyond that.

As we started producing plant material, we found from all of our partners in federal and state land management that they also have these shortages. We’re working on producing plant material and plugs for those partners as well. Beyond that, we’re looking at ways to keep land in the Walker River Basin economically productive on much less water, and we’re in a very unique position where we have this super strong incentive to dramatically increase the productivity per unit of water used, and really create a model that can be used by others and scale from the work that we’re doing.

I’m calling in today from a ranch that we own and operate here in Smith, [and] we’ve got a crop of Great Basin Wild Rye coming up that’ll be harvested for seed, and we’re going into field prep on roughly 100 acres of additional native seed production. Our goals with that are to reduce total irrigation demand while keeping land economically productive. We won’t have the same footprint that we’ve had historically on this ranch, but we will demonstrate that we can keep land economically productive while increasing the availability of much, much needed plant material for our region as well.

I want to ask about a pilot project [that] looks to retire groundwater in the Walker Basin. What does that ultimately mean, not just for the lake, but for farmers, ranchers and other water users in the region?

It’s important first to understand the role of groundwater in the Walker River Basin. In an average year, there is more land in production and more demand for irrigation water than there is water in the Walker River. And that’s been the case for quite some time in our region. Beginning in the middle of the 20th century, we began developing groundwater resources to make up the difference. There’s a lot of acreage in Smith, a fair amount of acreage in Mason Valleys that have some surface water rights, but not enough to actually grow multiple cuttings of alfalfa throughout the year, and that deficit is made up by pumping groundwater – and that has led to unsustainable withdrawals of groundwater from the aquifers in the region.

We had pretty severe drought in 2014-15, and those years led to domestic wells going offline in this region, and it led to an order from the [state of Nevada], effectively limiting people’s right to pump groundwater. So, if you had supplemental groundwater rights at that time, you were limited to pump 50% of the permitted volume. That was eventually struck down in court on some technicalities, but to this date, [it] remains the only region in the state of Nevada that has been subject to such a curtailment order. That’s in many ways an existential threat. The fact that the state can come in, and based on the state court ruling, it won’t be a haircut to all producers. It’s going to be turning the 50% of junior well users off, 100% of them. That’s existential for a lot of folks in our region.

We’ve also seen recent research indicating that as the groundwater tables pull down in Smith and Mason Valley, more of the river is being lost into the ground. We’re essentially drawing down the water table and pumping the river down with it. That leads to this really challenging cycle where you’re getting less surface water deliveries, so there’s more need to pump groundwater, and the more you pump groundwater, the less surface water deliveries we’re seeing.

The state has made clear that it’s a priority to interrupt that cycle, and the Conservancy’s already played quite a big role in that. We’ve done 24 permanent water rights transactions to date. In addition to surface water and land, we’ve purchased groundwater in the past and retired that groundwater. So, over the last decade, we’ve retired, or the technical term is relinquished, over 11,000 acre feet of groundwater. Pretty substantive.

The state in 2023 awarded the Conservancy a grant to carry out a pilot project to perform basically state funded retirement of groundwater rights. It’s the first time that we have been able to prioritize buying groundwater rights and retiring them, separately from surface water, as its own direct goal. And we’ve been blown away by the interest in the program. We had about three months to identify willing sellers [and] provide a list to the state, and initial funding was about $4 million for our region. We had about $36 million of groundwater come forward as interested in selling. That surpassed our expectations of how many interested sellers and the volume of water people would be interested in selling. I think it goes to show that in a region where there’s a clear risk of regulation long term, people are willing to come to the table on a market solution to take water rights off the books and reduce total irrigation demand.

There was [also] a $14.9 million trust that’s funded by the National Fish and Wildlife Service to help protect water rights in perpetuity. What is that trust? How does it work exactly?

In the Walker River Basin, if you have water rights, you pay basically property taxes on them. We call those assessments, and that pays for all the infrastructure to deliver water, as well as regulate water in the region. One of the concerns when we first started doing environmental water transactions is what happens to the revenue, to the irrigation district, to the U.S. Board of Water Commissioners from those property taxes. From the beginning, we’ve committed to continuing to pay those assessments or those taxes on water rights acquired through the Walker Basin restoration program. And so that trust effectively endows a fund that will support our long-term commitment to pay those assessments, as well as to protect the administration of protecting those water rights instream as well.

What does the future of Walker Lake and the Walker River system look like to you? What’s your ultimate vision? Do you see the lake ever returning to full status, and what would it take for that to happen?

You know, we keep praying for rain and praying for snow. Our vision of [the] Walker River Basin and Walker Lake is a balanced one. We have increasing climatic variability in this region, and it’s putting stress on our water resources. That brings stress not just for agriculture, but for developing domestic water sources, for developing any kind of industry in our region. Water is the limiting factor for all kinds of economic development throughout the region.

At the Conservancy, our vision for the Walker River Basin, is ten years from now, a river that has increased flows, leaving Mason valley of about 50,000 acre feet per year. We’ve got a clear trajectory for reestablishing a fishery at Walker Lake. We’ve got a river between Mason Valley and Walker Lake that exists again, continuously for the first time in 50 years. We’ve got public access to the river corridor as well. Through our program, [we] have really prioritized acquiring land when there’s direct conservation value there, or key public access opportunities, and we will continue to develop both of those as we go forward.

I want to wrap up by asking about the upcoming open house later this month [June 25]. Tell me a little bit about that event, and anyone who’s interested in in taking part, what do they need to know?

So, June 25 we’re doing an open house here at our seed farm in Smith. It’s a short drive, about, an hour and 10 [minutes] if you’re in Reno, [a] lot less if you’re in Carson or Carson Valley. We really encourage folks to come out. We’ve got about two miles of river corridor here in Smith and working on converting a legacy hay farm into a model for how we can keep economic productivity in our region on reduced water use while increasing availability of seed. We’ve got a tour of our nursery as part of that. We’ve got a tour of our native seed production as part of that, as well as [a] trip down to the river.

If you’re reading this, I really encourage you to get involved. Whether your passion is water, whether your passion is plants, or whether your passion is something completely different, get involved and put your voice forward and your time forward for causes that you care about. We’re at a really critical juncture as our region grows to ensure that the things that folks enjoy so much, in terms of public access, outdoor recreation, and quality of life, continue to be strengths for our region. Get involved and take ownership of the resources in your region.

To learn more about the Conservancy, its projects and the upcoming open house, visit their website at walkerbasin.org.

This interview was edited slightly for length and clarity.

Republish our stories for free, under a Creative Commons license.